Len Ballantine

Reprinted from the Apr-May-Jun 2005 issue of THEME

I play the piano at our corps and people often tell me that they love listening to me play. While I am grateful for the compliment, I think they are not really aware of the whole dynamic of my role. If I’ve done my job well, if I’ve truly accompanied the service as I am going to reveal to you, then what they are responding to when they say they like to hear me play is really about the seamless enhancement of the worship experience, and not about my playing at all. They are sensing that they have been helped in what they are doing . . . by what I am doing. And that is a very different thing than merely delighting their auditory senses or wowing them with dexterity. Playing the piano for worship is a ministry in itself and requires me to enter into each phase of the worship time, into each phrase of the sung material, and into each place where discontinuity threatens to distract the worshipper off course.

This is an intuitive style, that is, it is a response to the worship experience that is going on all around me. As such, it is a felt sense, and requires the player to be at one with the instrument and at one with the purpose and direction of the service. Intuition cannot be planned for by writing down instructions on the order of service, but, of course, the more one knows about what’s coming, the better one’s intuition can function. By definition, intuition is linked to understanding, spontaneity, readiness, willingness, and of course, ability. This art is more than going with the flow. Indeed, intuitive response drives the musicians to direct, to add to, and enhance that flow.

This is an extemporaneous style, that is, it is not written down, and if it were, it would be very off-putting in its complexity. The pianist’s craft is tactile and the fingers need to be comfortable with common progressions in most keys. As well, the pianist will want to possess some basic tools of improvisation such as being able to play by ear (sense where the harmony is going) and be able to ‘fill out’ the part without musical notation.

Key technical considerations of (modern) piano worship styling

There are two areas to cover in consideration of worship styling for piano:

(A) Technical aspects of playing.

(B) Functional aspects to which this technique is applied.

1. Strength & confidence…

...into the keys, weight, sonority… why? So that the cues are clear; so that the leader knows where you are and that you are with him/her; so that the congregation knows where to start, what the tempo is, and what the style is going to be. Your playing is not an accompaniment, in the background, subordinate, merely supportive. Rather it is an integral component, a motivator, an amplifier, a conveyor of emotion, a facilitator of worship in its own right. That kind of role cannot be accomplished by a weak hand or a weak spirit!

2. Rhythmic playing

So much of today’s music is rhythmic in nature. Playing rhythmically is a special art that enhances the character of modern songs. In its simplest form this refers to a pointed, vital, tactile, that is, accented approach to playing. In this, it is a muscular approach and runs counter to the notion of smoothness which is generally prized and taught to students as something to strive for.

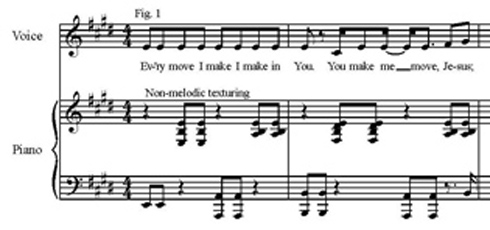

3. Non-melodic texturing

By this I mean the function of playing chords in a rhythmic fashion, filling out the accompaniment in textured manner, without playing the melody

Many keyboard players have gotten into the church accompaniment business by playing the hymnal, that is, melody on top, simple harmony in vocal form below.

All church hymnals are written this way -- melody in the right hand. Good for traditional organ approach, because the organ sounds in octaves and has different timbres, creating a larger-than-life background for singing. Not good for piano because there are only basic note combinations, in a vocal arrangement, after all. The hymnal/song book rendition, even contemporary arrangements, are written with a pretty basic level skill-set in mind, and even then they are too difficult for many well intentioned players.

4. Simple arpeggiation or broken chords…

...create texture and movement in the music. This is a highly useful skill for pianists to develop and is the basis for all attempts to ‘fill out’ the arrangement. Its effect is like finger-picking Vs strumming on the guitar.

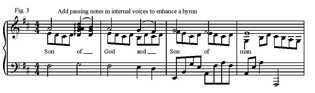

5. The passing note

If all else fails and you cannot break into the realm of playing by ear, try adding passing notes to the existing arrangement. Add them on internal voices. Add them in the bass line.

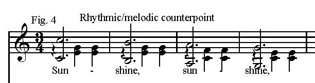

6. Rhythmic/melodic counterpoint

Used when the rhythmic life of the song is part of its character as in a marching song (after time) or a waltz. It is accomplished by playing the melody in octaves whilst using the other fingers of the right hand to play the rhythm.

7. Harmonic richness

Chord choices should be interesting but not obtrusive, and definitely not idiomatic, (i.e. not jazz or cocktail style). Just plain accompaniment, in the main, that people can harmonize to.

A good way to practice standard chord progression in various keys is to try the cadencial formula I-IV-V-I in all major and minor keys. This will give you a tactile sense of home base wherever you are. Another way to get started in this adventurous journey is to use alternate minor chords in place of the plainer major chords, i.e. Try using ii instead of IV, iii instead of I or V, & vi instead of I.

8. Suspensions (sus2 and sus4)...

...are useful in creating space and interest and musical tension in the manipulation of the flow of the music. Basically, the suspension is a modern version of the plagal or church cadence, IV-I, and provides a decidedly ‘Amen’ feel to the music, whether perceived or not.

9. Musicality

This includes phrase shape, room to breathe, emphasis, word painting in context, adding to the drama of a high moment with flourish, arpeggio, expansion stuff, all to enhance and lift the participant, and help them experience where the song is trying to take them. Ask yourself “what is this moment supposed to achieve?†Add to the drama of the low moments with diminution of means so that the congregant is aware of the room, the human voice, his own place in the space.

10. Contrast...

...is the key watchword of all music making. High/low ... thick/thin ... sustained/rhythmic ... melodic/non-melodic ... loud/soft, etc. I am conscious of always manipulating and controlling contrast, to keep the music well ventilated, full of air, full of changes, full of interest. If I don’t look for points of contrast in the music it will soon devolve into an annoying sameness, a drone, a static thing that is just a lump, always there and unyielding in its predictability.

Key functions required in (modern) piano worship style

Continuity

Continuity refers to the connective bits that join the parts of the service together. It is highly desirable to create a continuous flow in the worship journey. Continuity is a musical means to that, as is spoken continuity. Why? Because songs start and stop, scriptures lasting two or three minutes are read, offerings are taken. No matter what we do to disguise the sandwich feel, our worship inevitably ends up being one. Thus continuity from the keyboard has become a way of generating a longer flow, a sense of being involved in one thought, or at least a continuous flow of thoughts which bring us to where we want and need to be.

(a) Introductions

The simplest form of continuity is the introduction, where a semblance of the tune and reference to the key prepare the congregant to sing. The style of the song should be mirrored in the introduction so that the mood and intention of the music is prepared as well.

(b) Extensions

Continuity which sustains momentarily the mood or momentum of a song we will here call extension. This technique allows the song to have an after-life which sustains the feeling or energy and allows the congregant to be let down gently, or respond prayerfully or in spontaneous applause. Most songs simply need to come to a conclusion, but when there is sufficient heart and energy intentionality present, the worship leader may feel that extension is appropriate. How do you tell? Intuition.

(c) Lead-ins

Continuity which brings us from an extremely sensitive moment of dead silence back into participation mode is what I call a lead-in. This is often called-for after the sermon, as a bridge into the response time. It is a tricky moment because some people will be lingering in reverie, in prayer, in a stunned or a numbed mode of consciousness. The role of piano here is to create an unobtrusive start which eases the worshipper out of the lethargy of listening and back into the reality of time and space. Gradually, the piano adds interest and creates in all a growing sense of needing to join in. Simply put, we take the congregation from 0-60 in six seconds, or whatever the case may be.

(d) Transitions

Continuity added between songs is referred to as transition, and involves getting from here to there. Why do we need the music to create transition? Because, we are here but we want to go there. And without a transition we would simply be dropped in it. Again the song sandwich. Pierre Boulez quoted, “All works of art have a beginning, a middle, and an end.†So it is with worship. Our role is to transport the congregant from one moment to another in an effort to keep him on track, focused, of one heart and mind with the intent of the service. Transitions are helpful in creating seamlessness.

(e) Transitions involving MODULATION

Modulation is a wonderful tool in creating a dramatic and natural enhancement to the flow of worship. The purpose is to get us to the next key and make us feel that the next key is inevitable, fresh, needed. Most modulations will need to be worked out ahead of time, and if successful the congregation will be ready and interested in where we are going.

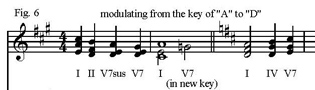

Understanding the function of the dominant seventh chord is key here because of the gravity or pull the V7 exerts as it prepares the ear for resolution.

Keys that are a fifth apart (where the 2nd key is a perfect fifth below the first) provide a natural modulation and really need no transition chord at all, although some pianist will present the V7 just to let people know there is a shift coming.

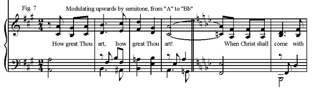

A modulation upwards by a half-step can be part of the dramatic strategy of shaping a song. Here the final tonic chord of a verse is followed by the V7 of the new key, which conveniently contains the tonic note of the previous one. The “half-step upwards†modulation can be seen to add a positive impact to the last verse of a song. It has the effect of lifting us out of the lethargy that sometimes sets in when we sing familiar songs frequently, and adding interest if there happens to be a lot of verses to the song being sung.

More distant modulations will take more than a mere V7 to establish. To this end, basic progressions of chords need to be practiced until their tactile function is mastered. Practicing the progression II-V-I in all keys will build skill and comfort in the working-out of modulation bridges from any key. This progression is a solid one because it is comprised of two very stable moves in the cycle of fifths. (i.e. II is really V of V in the new key).

Pivot chords bridge two disparate keys by being common to both. In other words, you’ve got your old key, and you’ve got your new key, and between the two you need to build a bridge using something common to both sides.

(f) Prayer backing

Continuity can also be used in the form of backing for prayer. Some worship leaders like this effect, some do not. Never assume that the worship leader would want this. Personally, I hate it. I hate it when someone plays while someone prays because immediately I start to listen to the music (with a critical spirit). Not a good thing to do if you’re supposed to be praying. I sometimes use it if I’m leading from the piano, that is, doing both the praying and the playing. I do it when I know the prayer will be short and I’m in control of that.

It is a delicate job, a difficult job, especially on a piano as opposed to a digital keyboard where sustained pads can be used simply to freeze the moment. The pianist who creates continuity for prayer must avoid becoming a distraction, avoid just playing the tune the same way as you just sang it, (i.e. avoid same level, same tempo, same weight/loudness). The prayer backing should be quieter, slower, create as little interest in itself as possible, contain only a merest outline of the tune.

Slow arppegiated chords can be used, perhaps in conjunction with a two-chord pattern (e.g. I-IV repeated).

Occasionally the leader may ask for backing during prayer with the intention of singing the prayer chorus again. In this case, the level should be loud enough to keep people on track with the passage of the song, so they know when to come in. I generally play the chorus once and wait to see if the leader jumps in. Rarely do I have to play it twice.

I don’t suppose I’ve ever encountered a roadmap or a set of building instructions without feeling that initial shudder of fear at the prospect of beginning the unknown. Perhaps these notes have struck you that way. Maybe all these words have nowhere to sit and the business of playing by ear is as illusive as ever. What I have found is that as soon as I take even one step forward I begin to see how things go together. After trying a few things, getting my hands dirty, it isn’t long before I’ve turned a few corners or assembled a few nuts and bolts. The journey takes shape. My confidence rises. I see the light at the end of the tunnel.

If there is even one exercise in the above that seems to make sense to you, sit down and do it! Master it. Build your confidence before you take on another. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither were pianists who can play in the dark. Hopefully these pointers will help turn on some lights for you.